A big part of a material’s features is thermal motion. This is especially true for semiconductors, whose conduction limits change a lot with temperature. It is possible for solar cells to work in temperatures ranging from below 220°C to above 80°C. For use in space, the temperature range can be even wider. Materials used in traditional solar cells, like silicon, CIGS, and GaAs, slowly lose their ability to work when the temperature goes up. But lead halide perovskites are more complicated because they are very active systems. The amount of temperature motion has a direct effect on the crystal structure of lead halide perovskites and the dynamics of its parts. This changes how flaws form, how ions move, how charges are transported, how insulating the material is, how it recombinates, and how it interacts with other materials.

Temperature can be changed to learn about the physics of the system, like the activation energies of different processes. When the temperature is low, new effects show up that help us understand the basic science of perovskites. Higher temperatures are helpful for studying how crystallisation works and how decline happens, but they need to be stopped.

This chapter talks about how temperature affects the crystal structure of lead halide perovskites. It also talks about the movement, binding, and importance of organic ions, as well as phase changes, thermal expansion, optical properties, and stability. Finally, it talks about how these things can affect how well perovskite solar cell devices work.

Crystal structure and phase transitions

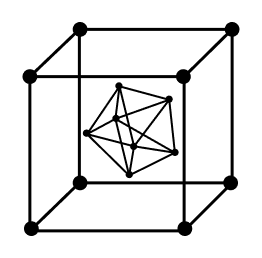

The main thing that determines the properties of perovskite solar cells is their crystal structure. These properties are limited by the thermal energy that is available and how it affects the space that the structure’s parts occupy, the excitation of the excitable, and the energetics of the bonds between atoms that are close to each other. The normal perovskite structure is made up of ABC3 atoms, and the perfect structure is cube-shaped and has a backbone made up of BC6-octahedra that share corners and cuboctahedra that hold A-cations. The structure depends on how big the three ions are compared to each other. The idea of a tolerance factor, t, can help explain this.

There are many similar perovskite chemicals that show promise as PV materials. Of these, methyl ammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) has been studied the most. Based on the tolerance factor, it should have a tetragonal shape, which is also the case when it is at room temperature. At room temperature, the structure of organic-inorganic lead halide perovskites is not at all fixed. Instead, it is a very dynamic system where the atoms move around a lot around their equilibrium points. The main reasons for this change are that the organic MA/FA ions don’t have a circular shape and have a hard time attaching to the artificial backbone of the PbI6-octahedra. The halogen atoms make up a nonuniform energy environment that the organic ions live in, which is made up of cuboctahedral gaps. In this scene, the MA ions connect with dipoledipole interactions, with NH?I interactions being the greatest. These interactions have a number of energetically favourable direction. Because the interactions are weak, it doesn’t take much energy to move the MA-ions from their chosen positions. This lets them jump between preferred positions in the halide cages.

Moving the MA ions around in MAPbI3 takes between femtoseconds and picoseconds at room temperature. During this time, there is a difference between the molecule dipole moving more slowly relative to the iodide lattice and moving faster around the crystal axis. Flaws can make things even more complicated because the spinning dipoles show a way to screen charges by aligning towards them. Because of this, mixed perovskites have a high dielectric constant, which helps explain why they don’t have much exciton energy and aren’t excitonic at room temperature. It is still not clear how the organic cation can be reoriented, especially since perovskite solar cells made of only artificial materials have been made, though they are less efficient.

It is still not clear how the organic dipoles organise themselves into ferroelectric regions and how this changes the separation, transfer, and exchange of charge carriers.

A lot of people are interested in the perovskite structure because it can balance greater entropy through chance and energy gain through group organisation. The chance of beating the activation energy for turning goes up as the temperature goes up. This means that the spin goes faster and columbic interactions with fixed charges or external fields have less of an effect on the total energy. This causes the dielectric constant and the chance of group ordering to slowly go down.

The energy map in the halogen cage can be tuned to change the makeup of the perovskite by slowly swapping the halogen or organic ion. This can change how the rotations and activation barriers behave. The heat energy won’t be able to get past the spinning barriers if the temperature is low. This means that the organic ions will freeze in place, most likely in a straight line. For MAPbI3, this changes the phase to an orthohombic phase at low temperatures around 2113 °C. This phase has a much lower dielectric constant, higher exciton energy, less motion, and doesn’t seem to be useful for solar cell uses.

Higher temperatures can make the thermal energy much higher than the weak bonding energy between the organic ion and the halide cage. This lets the organic cation rotate almost freely. Because of this, the organic ions’ form over time tends to become more spherical, making them take up more space. This causes a change in phase from a tetragonal to a cubic high temperature phase, which can be seen in diffraction tests at 54 °C.

The organic ions don’t have a spherical molecule shape, even if their time average shape is spherical at higher temperatures. The local structure might not be the same as the cubic time average seen in XRD and Raman readings if the artificial lead halide framework can move around with the spinning of the organic ions. It has been shown through simulations that the lead halide structure can adapt to motion quickly enough for this to be true.

On the time scale of electronic changes, the material may not experience a cubic world very often, but rather one that is changing and twisted into a tetragonal shape. It fits exactly with what we saw when we looked at how the phase change of MAPbI3 from the tetragonal to the cubic phase at B55 °C didn’t cause any big changes in how it absorbed light or how it worked as a device.

Thermal expansion coefficients

With X-ray diffraction, phase shifts in perovskites can be studied. This has been done for MAPbI3 and a few other mixtures. Around 54°C, polycrystalline MAPbI3 changes phases, and around 55°C, it turns into single crystals. This happens between a tetragonal phase and a high temperature cubic phase, which is interesting because it is in the temperature range that solar cells can work at. The tetragonal phase and the cubic phase have XRD patterns that are similar but also very different. For example, some double peaks in the tetragonal phase merge into single peaks in the higher symmetry cubic phase.

The experimental data in Fig. 8.2B shows how the XRD pattern changes during the phase transition. When the temperature is changed from room temperature to 80°C several times, this change can go both ways, at least for a short time. It’s still not clear if the change could happen again after the thousands of rounds that perovskites in solar cell modules would go through during their lives.

In actual XRD data, there is a shift in the peak places towards smaller angels at higher temperatures. This means that the lattice is getting bigger. The tetragonal structure grows along the a-axis and shrinks along the c-axis in a straight line as the temperature rises. Once the phase change happens at 54°C, the a-axis keeps expanding, pretty much without a break. This fits with a slow and gentle phase change based on the spinning energy of the MA ions in the lead-halogen octahedron. It also means that the phase change doesn’t need any atomic reorganisation, like breaking or making covalent or ionic bonds.

The original cell volume can be found by using the lattice factors. This volume also grows linearly with temperature. The thermal expansion coefficients are easy to find when you know the lattice parameters and the cell volume as a function of temperature. The linear thermal expansion coefficient in the length dimension L is given by Equation 8.2, and the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient, αV, is given by Equation 8.3.

From a structural point of view, the change from the tetragonal phase to the cubic phase doesn’t seem to be a big deal. It is better to stay away from it if you can. If you replace some of the methyl ammonium ions with bigger ones, like formamidinium ones, you can change the tolerance factors. This will move the phase transition to lower temperatures, making the cubic phase more preferred even at room temperature.

Optical properties

Charge carriers are made in solar cell materials through optical absorption. The absorption peak for MAPbI3 gets sharper and moves to lower energies as the temperature drops. Measurements of steady-state photoluminescence show this behaviour. If you change the absorption start, you also change the band gap, and for MAPbI3, the band gap gets smaller as the temperature goes down. The gap between the bands changed from 1.61 eV to 1.58 eV when the temperature went from 80°C to 2190°C.

The band gap doesn’t get smaller as the temperature rises for most typical semiconductors. This is because of changes in electron-phonon interactions and thermal expansion. MAPbI3, on the other hand, may behave in the opposite way because its valence states don’t connect with other atoms. When the temperature drops, the space between the atoms gets smaller. This makes the antibonding states more energetic by breaking their orbitals more.

Around the phase transition temperatures, like 54°C for the tetragonal to cubic transition and 2113°C for the orthorhombic to tetrahedral transition, no changes or breaks were seen. This behaviour fits with the idea that phase changes are slow and gentle. There is a difference in temperature of almost 300°C, so a change in the band gap of 0.03 eV is not very important in real life. Changes in the visual features of the perovskite cannot explain why the device’s performance changes a lot with temperature.

Degradation at higher temperature

In the past few years, perovskite solar cells have shown amazing levels of efficiency. However, devices still need to be stable over the long term in order to have a big effect on technology. Some of the things that can break down perovskite are light, air, water, and metals moving from connections. A rise in temperature is a major cause of decline because it can break down into solid PbI2, methyl ammonium, and hydrogen iodine, which can then disappear in the gas phase. The methyl ammonium could also break down into ammonia and methyl iodine, which is another possible route.

It’s not easy to find the exact temperature at which MAPbI3 breaks down. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) shows that MAPbI3 is steady up to about 200°C. However, it seems to have problems at much lower temperatures in most places. This difference is partly due to timing—only a small amount of the material needs to break down before the device stops working properly—and partly to mixed effects—rising temperatures can speed up breakdown along other routes that need light or moisture.

Many times, the cooling temperature for MAPbI3 crystallisation is 100°C, which is possibly too low to break down the perovskite by itself. In some situations, a small amount of extra lead iodine can form. This is good for the performance of the device as long as the other breakdown products are let out in the gas phase.

It looks like the MA ions are what make MAPbI3 break down easily at high temperatures, and people have tried to change them. One way is to use all artificial perovskites with Cs as the cation. These have already been made and are more stable at high temperatures. The cubic α-phase of FAPbI3, on the other hand, changes quickly into a yellow version at room temperature, making it useless for PV uses.

Some of the best mixtures are FAMA perovskites that are doped with Cs and/or Cs-Rb. These have shown good stability when exposed to light at 80°C. This shows that a small amount of MA-ions can help crystallise and stabilise the FA perovskite, and they might not really hurt the material’s thermal stability up to 80°C as long as they are present in small amounts.

Device performance

Device function is the most important temperature-dependent factor in how well a solar cell works. MAPbI3 has been looked into by several groups both at room temperature and below. When the temperature was raised from room temperature to 80°C, the most efficient level was found at 3035°C. As the temperature went up, η, Voc, and Jsc slowly went down, while FF reached its highest point around 60°C. Most of the performance loss was gone when the cells were brought back to room temperature, showing that they could be reversed to a certain extent.

The observed drop in efficiency as the temperature went up was about 0.08% K21. Based on how other solar cell materials behave, it is likely that the performance will go down at higher temperatures. But the size is bigger than what was seen for silicon, and it’s big enough to be a problem since only 80% of the performance at room temperature is still there at 60°C. This is a problem, but it shouldn’t stop people from using perovskite solar cells outside. This is especially true since gadget performance and stability are changing so quickly, so it’s reasonable to think that things will get even better.

At higher temperatures, the open circuit voltage is likely to go down because of more entropy. This lowers the electrochemical energy of electrons and holes in the conduction and valence band, makes the Fermi-Dirac distribution wider, and moves the quasi-Fermi levels farther away from the band edges. This is the direction for data up to 50°C for common devices like FTO/TiO2/mesoporous TiO2/MAPbI3/Spiro-MeOTAD/Au.

It’s worth wondering if the perovskite phase, especially the change from tetragonal to cubic seen for MAPbI3 at 54°C, has an impact on how well the device works. As the temperature goes up, there is a steady decreasing trend in ·, Vov, and Jsc. The cubic phase might be helpful, since the best solar cells on the market right now are made of perovskites that are high in formamidinium. But the trend in temperature is bigger than this effect, and the performance boost at 60°C is only a small part of the trend that is going down.

The study looks into how well perovskite solar cells work at different temperatures. When the temperature goes up, the Voc goes down, and when the temperature drops below 2160 C, it goes to zero. This means that there are fewer charge carriers, either because the rate of recombination has gone up or because there are fewer chances for charge carriers to be created by exciton dissociation. Down to 2120 °C, the FF drops widely, and the IV curve changes from the form of a solar cell reaction to a straight line. This shows a very resistant behaviour, which for temperatures below 280 C might be due to a high series resistance.

It also worked best when the temperature was close to room temperature, even though the performance dropped to 280 ˺C, which was still pretty low from a practical point of view. In contrast, this behaviour is different from common PV materials like silicon, where a lower temperature is always better for device function.

It was found that the Voc behaviour and the higher series resistance had nothing to do with each other. This suggests that there are more than one way that performance drops at low temperatures. One reason for the higher resistance could be that thermally triggered charge hopping in the Spiro-MeOTAD hole conductor is slowing down. This fits with reports that conductivity and hole motion decrease as temperature drops. Other possible processes involve the perovskite phase. For example, THz spectroscopy shows that the mobility increases at lower temperatures. However, charge transport and recombination at grain boundaries may limit how well the device works.

In real life, higher temperatures make cells work less well, which is what we would expect from other solar cell methods. It was seen that MAPbI3 is decreasing at a rate of 0.08% K21, which is high but not unbearably high. It’s also not stable at high temperatures. Room temperature is like Goldilocks’s area for perovskite solar cells. This is because of the unique physics of perovskite and also because this is the temperature where the best performance has been achieved.

Leave a Reply